The lack of political independence of the media is the worst risk identified for Malta in the annual Media Pluralism Monitor report published by the international Centre for Press and Media Freedom, which notes a deterioration of the situation in the country since 2016.

The political independence of media indicators scores a very high 83% risk level (the higher the score, the greater the risk). This category assesses the existence and effectiveness of regulatory safeguards against political bias and political control over media outlets, news agencies and distribution networks.

They seek to evaluate the influence of the State (and, more generally, of political power) over the functioning of the media market and the independence of public service media.

The worst risk indicator is “commercial and owners’ influence over editorial content” in particular of public service media – 79% risk.

Other risks are: cross-media concentration of ownership (69%), access to media for minorities and for people with disabilities (75%), and media literacy (79%).

The report is critical of the Malta Institute of Journalists (IGM) saying it was not effective in safeguarding editorial independence.

While the protection of freedom of expression indicator acquires a relatively low 24% risk score, this represents a 15% increase compared to 2016 when it was only 9%.

The main reason for this increase is the assassination of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia on 16 October 2017, which was seen to have had a chilling effect on freedom of expression.

“It should also be pointed out that shortly before her assassination Caruana Galizia and other Maltese media outlets reporting on the Panama Papers and Pilatus Bank (including The Shift News which has carried on some of Caruana Galizia’s work) were attacked with Strategic Lawsuits against Public Participation (SLAPP) actions lodged in third countries,” the report states.

The report notes that Caruana Galizia’s assassination “starkly brought to light several structural issues this EU Member State is facing, not solely in relation to media freedom and media pluralism, but more generally from a rule of law perspective”. She had faced had faced “libel suits, intimidation, and death threats for years”, the report states.

The Media Pluralism Monitor 2018 report was conducted in the 28 EU Member States, as well as Serbia, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYRoM) and Turkey.

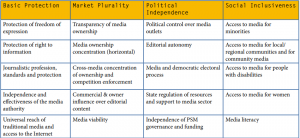

Risks to media pluralism are examined in four main thematic areas, which are considered to capture the main areas of risk for media pluralism and media freedom: Basic Protection, Market Plurality, Political Independence and Social Inclusiveness.

The fact that a medium risk has been detected in the area of ‘basic protection’ is a reason for concern, as this area encompasses the fundamental conditions that are needed to exercise journalism and individual freedom of expression.

The journalistic profession, standards and protection indicator scores a medium risk (36%), up 5% compared to the low risk score (30%) of 2016. “This, too, is directly linked to the murder of Caruana Galizia,” the report states.

The ‘protection of the right to information indicator’ scores a medium risk (56%). Investigations reveal that journalists sometimes have problems accessing government information, “since the procedures are often prolonged, making the information outdated by the time it is revealed,” the report notes.

The State regulation of resources and support for the media sector indicator scores a medium risk (50%), largely due to the fact that there is no legal framework for, nor is there any transparency in, the allocation of State advertising.

“The government uses state advertising in the pre-election period, but also all year round, as a form of political advertising that aims to channel money to certain media outlets,” according to the report.

The independence of public service media (PBS) governance and funding indicator scores a high risk (83%). The report notes there are also no safeguards to prevent the influence of commercial interests over the appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief.

Attention is drawn to advertorials put forward as news: “Although there is a law prohibiting advertorials, experts suggest that it is not effectively implemented and hidden advertising in the media sometimes occurs.”

Another issue that contributes to the risk is the weakness of legislation on the protection of whistle-blowers. Malta’s Protection of the Whistle-blower Act came into force on 15 September 2013, but the law does not protect whistle blowers if they fail to first resort to internal reporting procedures, or if they report to the press or other media. The case of former FIAU official Jonathan Ferris is an example.

The report also notes that since Malta is still one of the few countries in Europe that, to date, has no policy on media literacy, “we reiterate the 2016 recommendation [that] in order to empower citizens with critical understanding and the skills needed for active participation in contemporary information exchange, policymakers in Malta, as well as academia and the media industry, should foster and encourage an inclusive discussion with a view to adopting a comprehensive media literacy strategy”.